Workforce Size & Demographics

Perhaps most worrying of all of the symptoms identified in this section, is the fact that the pure physical capacity of the construction industry to deliver for its clients appears to be in serious long-term decline. This issue is dealt with further in section 2 of this review, but a combination of an ageing workforce, low levels of new entrants (linked to industry image - see page 40) and an overlay of deep and recurring recessions which induce accelerated shrinkage, now threatens the very sustainability of the industry. It is potentially in danger of becoming unfit for purpose.

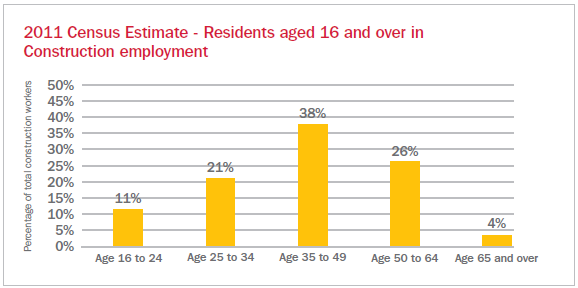

In 2015, the Arcadis paper, People & Money,16 highlighted labour availability within construction as being the biggest constraint on the industry over the next five years if it is to achieve the Government's aspiration of one million homes. It demonstrated a need to recruit another 700,000 people to replace those retiring / natural leakage to other industries, this is in addition to the extra workforce needed of 120,000 to deliver capacity growth. The 2011 Census data (Figure 13) shows us 30% of the workforce at the time aged over 50 therefore if we look to ten years from now in 2026 this represents around 620,000 people, based on the construction classification used, who will have retired from the industry.

Figure 13: From Nomis, 2011 Census estimates, ONS Crown Copyright Reserved, Accessed April 2016

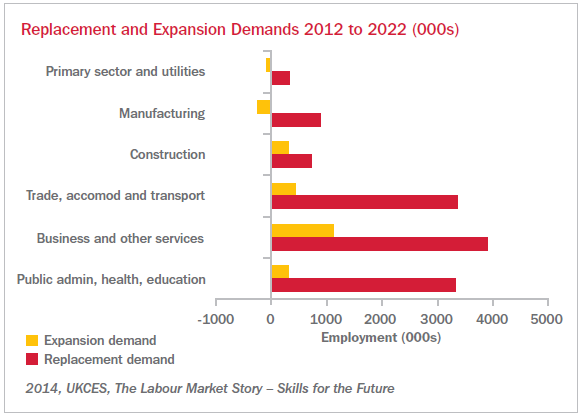

Figure 14: From The Labour Market Story: Skills for the Future, UK Commission for Employment and Skills, July 2014

Figure 14 from UKCES shows the number of replacement demand needed in the construction industry as being more than double the expansion demand.

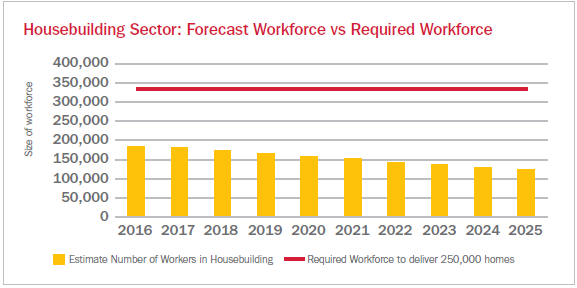

We can already see that based on the current situation of an 'ageing workforce' and the need to deliver at least 250,000 homes each year, Figure 16 highlights that we are a long way from having the right size of labour.

It is worth noting however that despite the headlines above, the level of stress created through labour led capacity shortages is geographically highly sensitive. The most acute problems align with cities and conurbations where economic activity and GDP contribution is highest. The construction skills crisis can therefore be characterised as a national problem but with regional hotspots. London's particularly challenging construction labour market issues cannot be ignored due to its importance to UK plc.

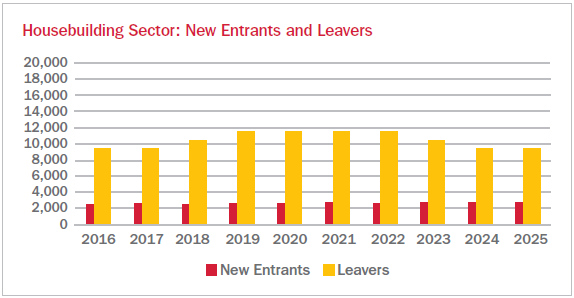

On the basis of a looming demographic 'time bomb' combined with the fact that industry productivity is not improving as set out on page 13, this means continued pressure is still being put on workforce replenishment and expansion as being the solution to the problem. This must now surely be seen as increasingly unrealistic in the light of the projected imbalance between workers leaving the industry and those joining as well as the overlay of a likely Brexit induced reduction in new migrant labour flows and possible risks to retaining our current migrant work force.

Figure 15: From Cast presentation at ULI UK Capacity Conference, 26 April 2016

Figure 16: From Cast presentation at ULI UK Capacity Conference, 26 April 2016

The impact of Brexit on construction has already been debated at large in the weeks spent finalising this review. Although it is likely that certain markets such as London, which are more heavily reliant on European tradesmen and professionals, will be adversely affected, the reality is that the relative proportion of migrant labour as a component of overall workforce was not going to be large enough to offset the size of the gathering problems ahead and was never the solution to the more deep-seated problems identified.

___________________________________________________________________

16 People & Money: Fundamental to unlocking the housing crisis, Arcadis, 4 June 2015.