The Pensions Regulator

135. The Pensions Regulator had an active interest in the Carillion pension schemes for the last decade of the company's life. While it was involved in negotiations between Carillion and the Trustee over the 2008 valuation and recovery plan, this involvement was "less intense" than its "proactive engagement" on the 2011 valuation.406 Following the July 2017 profit warning, TPR participated in a series of meetings to discuss the company's deferral of pension contributions.407

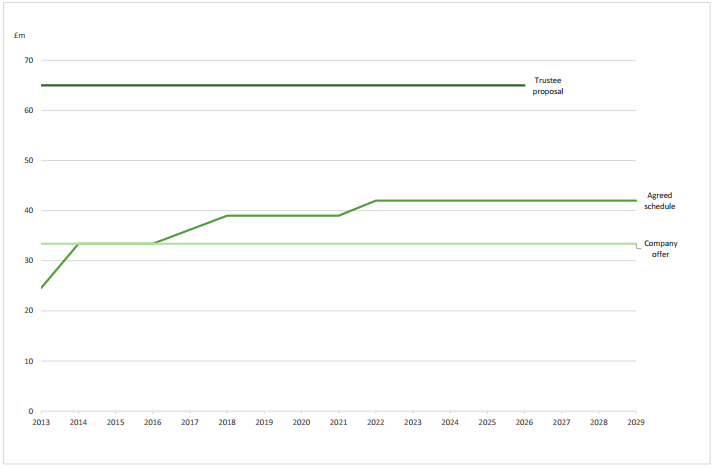

136. Earlier in this report, we found that, having adopted an intransigent approach to negotiation, Carillion largely got its way in resisting making adequate deficit recovery contributions following the 2011 valuation. TPR argued, however, that its involvement led to an increase of £85 million in contributions by Carillion across the recovery period.408 This figure is derived by comparing Carillion's initial offer of £33.4 million for 16 years with the final agreed plan, which had contributions rising from £25 million in 2013 to £42 million by 2022. To what extent TPR were responsible for that increase is unclear. What is not, though, is that the £85 million was a long way short of the additional £342 million the Trustee was seeking through annual contributions of £65 million. The agreed plan was also heavily backloaded, with initial contributions of £33 million matching the company's offer and steps up in contributions only occurring in later years, when it would regardless be superseded by a new valuation and recovery plan. Gazelle described the TPR's intervention as "disappointing" and expressed bafflement at how Richard Adam "managed to persuade the Pensions Regulator not to press for a better recovery plan".409

Figure 7: 2013 pension deficit recovery plans

Source: Analysis of Trustee minutes and scheme annual reports

137. If a company is failing to honour its obligations to fund a pension scheme, TPR has powers, under section 231 of the Pensions Act 2004, to impose a schedule of pension contributions.410 In 13 years, however, TPR has not used that power once with regard to any of the thousands of schemes it regulates.411 During the course of the 2011 negotiations, TPR repeatedly threatened to use its section 231 powers, making reference to them in correspondence on seven different occasions between June 2013 and March 2014.412 Carillion correctly interpreted these as empty threats. That is no surprise, given TPR's evident aversion to actually using its powers to impose a contribution schedule.

138. TPR were also willing to accept recovery plans in the Carillion schemes that were significantly longer than the average of 7.5 years.413 Carillion and the Trustee's agreed recovery plans averaged 16 years in both 2008 and 2011. TPR told us they do not want their approach to be "perceived as focused too heavily on the length of the recovery plan" and that longer plans may be appropriate where the trustees and employer have agreed higher liabilities based on "prudent assumptions".414 Carillion, however, explicitly rejected more prudent assumptions, but was still allowed lengthy recovery plans.

139. There is also little evidence that TPR offered any serious challenge to Carillion over their dividend policy, despite their guidance acknowledging that dividend policy should be considered as part of a recovery plan.415 In April 2013, TPR confirmed to both the company and Trustee that they were "not comfortable with recovery plans increasing whilst dividends are being increased".416 When questioned about Carillion's dividend policy, however, TPR argued Carillion's ratio of dividend payments to pension contributions was better than other FTSE companies and that they "cannot and should not prevent companies paying dividends, if that is the right thing to do".417 TPR argued this approach to dividends is in keeping with their statutory objective to minimise any adverse impact upon the sustainable growth of sponsoring employers in its regulation of DB funding. This objective, however, only came into force in 2014, after both the 2008 and 2011 valuations. Carillion's growth did, of course, not transpire to be sustainable.

140. TPR also has statutory objectives to reduce the risk of schemes ending up in the PPF and to protect member's benefits. The PPF expects to take on 11 of Carillion's 13 UK schemes, meaning the members of those schemes will receive lower pensions than they were promised. Even paying out lower benefits, the schemes will have a funding shortfall of around £800 million, which will be absorbed by the PPF and its levy-payers.418 TPR clearly failed in those objectives.

141. Following Carillion's liquidation, TPR announced an investigation into the company which would allow them to seek funding from Carillion and individual board members for actions which constituted the avoidance of their pension obligations.419 We await the outcome of that investigation with interest but question the timing. TPR had concerns about schemes for many years without taking action. There are also no valuable assets left in the company, and while individual directors were paid handsomely for running the company into the ground, recouping their bonuses is unlikely to make much of a dent in an estimated pension liability of £2.6 billion.420 The Work and Pensions Committee's 2016 report on defined benefit pension schemes found that TPR intervention tended to be "concentrated at stages when a scheme is in severe stress or has already collapsed".421 Carillion is the epitome of that.

142. The Pensions Regulator's feeble response to the underfunding of Carillion's pension schemes was a threat to impose a contribution schedule, a power it had never-and has still never-used. The Regulator congratulated itself on a final agreement which was exactly what the company asked for the first few years and only incorporated a small uptick in recovery plan contributions after the next negotiation was due. In reality, this intervention only served to highlight to both sides quite how unequal the contest would continue to be.

143. The Pensions Regulator failed in all its objectives regarding the Carillion pension scheme. Scheme members will receive reduced pensions. The Pension Protection Fund and its levy payers will pick up their biggest bill ever. Any growth in the company that resulted from scrimping on pension contributions can hardly be described as sustainable. Carillion was run so irresponsibly that its pension schemes may well have ended up in the PPF regardless, but the Regulator should not be spared blame for allowing years of underfunding by the company. Carillion collapsed with net pension liabilities of around £2.6 billion and little prospect of anything being salvaged from the wreckage to offset them. Without any sense of irony, the Regulator chose this moment to launch an investigation to see if Carillion should contribute more money to its schemes. No action now by TPR will in any way protect pensioners from being consigned to the PPF.

____________________________________________________________________

406 Qq653-4 [Mike Birch]

407 Letter from Chief Executive of TPR to the Chair, 26 January 2018

408 Q689 [Mike Birch], Q693, Q711, Q774 [Lesley Titcomb]

409 Letter from Simon Willes, Executive Chairman Gazelle, to the Chair, 29 March 2018, p 7

410 Pensions Act 2004, section 231

411 Letter from the Pensions Regulator to the Chair, 12 March 2018. Over 5,500 schemes are eligible for the PPF.

412 As above.

413 The Pensions Regulator, Scheme funding statistics, June 2017, p 7

414 Letter from the Pensions Regulator to the Chair, 12 March 2018

415 The Pensions Regulator, Code of practice no.3, Funding defined benefits, June 2014, p 3

416 Carillion single Trustee, Meeting between Trustee representatives and the Pensions Regulator regarding failure to agree the 2011 valuation, 29 April 2013

417 Q777 [Lesley Titcomb]

418 PPF letter to the Chair, 20 February 2018

419 Letter from Chief Executive of TPR to the Chair, 26 January 2018

420 £2.6 billion is the provisional estimate being made as to the deficit of the schemes on a section 75 basis, which is the size of the deficit according to how much would be paid to an insurance company to buy-out the liabilities. Although the section 75 debt will not be met as there are insufficient assets left in the company, that is the figure that becomes due on insolvency.

421 Work and Pensions Committee, Sixth Report of Session 2016-17, Defined benefit pension schemes, HC 55, p 4