The Pensions Regulator

180. Carillion consistently refused to make adequate contributions to its pension schemes, favouring dividend payments and cash-chasing growth. It was a classic case for The Pension Regulator to use its powers proactively, under section 231 of the Pensions Act 2004, to enforce an adequate schedule of contributions. Rt Hon Esther McVey MP, the Secretary of State for Work and Pensions, concurred with this assessment, telling us that TPR should have used that power.497 The other major corporate collapse the two Committees considered together, BHS, was also characterised by long-term underfunding of pension schemes. But the BHS case was different-the foremost concern in that case was the dumping of pensions liabilities through the sale of the company. The cases were, though, united by two key factors. First, a casual corporate disregard for pension obligations. And second, a pensions regulator unable and unwilling to take adequate steps to ensure that pensions promises made to staff were met.

181. The Work and Pensions Committee published a report on defined benefit (DB) pension schemes in December 2016.498 This drew on the joint inquiry into BHS and subsequent work on the wider sector. The Committee recommended that TPR should regard deficit recovery plans of over ten years exceptional and that trustees should be given powers to demand timely information from sponsors. It also recommended stronger powers for TPR in areas such as levying punitive fines to deter avoidance, intervening in major corporate transactions to ensure pensions are protected, and approving the consolidation and restructuring of schemes.499 Many of the recommendations of that report were adopted by the Government in its March 2018 White Paper, Protecting Defined Benefit Pension Schemes. The Government now intends to consult on the details of the proposed additional TPR powers.

182. The Work and Pensions Committee has commenced an inquiry into the implementation of that White Paper.500 The inquiry will be informed by the Committee's work on problematic major schemes, which has been primarily conducted through detailed correspondence and has considered:

• the long-term under-funding of pension schemes apparent in cases such as BHS, Palmer and Harvey, Monarch and Carillion;

• the suitability of buyers with short investment horizons, including some private equity firms, to assume responsibility for long term pensions liabilities, in cases such as GKN, Bernard Matthews and Toys R Us; and

• the potential risk to pension scheme covenants from corporate transactions, in cases such as Arcadia, Sainsbury's, Asda, Barclays, Trinity Mirror, Palmer & Harvey, and BHS.501

In the course of that work, it has become ever more apparent that, while some new powers are required, the problems in DB pensions regulation are primarily about the regulatory approach.

183. The Government and TPR recognise this concern and have pledged to act. The Secretary of State for Work and Pensions stressed that being " tougher, clearer, quicker" should be the "key focus" for a Pensions Regulator which would be "on the front foot".502 TPR told us that, while it accepted that "over the last decade there have been times when the balance between employer and scheme may not always have been right", it was "a very different organisation from five years ago".503 It is true that TPR has made changes:

• It has different leadership than at the height of its Carillion failings, Lesley Titcomb having been appointed Chief Executive in 2015;

• TPR has been given additional resources, including an additional £3.5 million in 2017-18 to support frontline casework;

• It has prioritised more proactive regulatory work and has set corporate performance indicators regarding quicker intervention in DB schemes that are underfunded or where avoidance is suspected;504

• Its performance measures now incorporate both the proportion of pension scheme members receiving reduced compensation and the extent to which schemes are adequately funded;505

• It has undertaken a period of self-analysis and change under the guise of the TPR Future programme;506 and

• TPR is under more political pressure to focus on its core responsibility of protecting pensions.507

184. These are positive developments, but what has this meant in practice? We were deeply concerned by the evidence we received from TPR, which sought to defend the passive approach they and their predecessors had taken to the Carillion pension schemes. Lesley Titcomb told us that TPR had secured an improved recovery plan for the schemes having threatened the use of section 231 powers.508 As we established in Chapter 2, the impact on the contributions received by the schemes was, at best, minimal. Mike Birch, said, with regard to section 231, "we do not threaten it when we do not think we would use it, so we were concerned".509 However, in 13 years of DB scheme regulation, TPR has issued just three Warning Notices relating to its section 231 powers, and has not seen a single case through to imposing a schedule of contributions. In these circumstances, it is difficult to perceive a threat from TPR of using its section 231 powers as a credible deterrent. We have little doubt that the likes of Richard Adam took TPR's posturing with a pinch of salt; other finance directors with his dismissive approach to pensions obligations would do likewise.

185. The hollowness of TPR threats is not restricted to its powers to impose contributions. The Pensions Act 2004 established a process of voluntary clearance for corporate transactions such as sales or mergers. Under this process, TPR can confirm that it does not regard the transaction to be materially detrimental to the pension scheme.510 It can therefore provide assurance that it will not subsequently use its powers to combat the avoidance of pension responsibilities, which could involve legal action and a requirement to contribute funds, in relation to the transaction.511 Though clearance applications were common in the early years of TPR's existence, however, they soon fell rapidly into disuse:

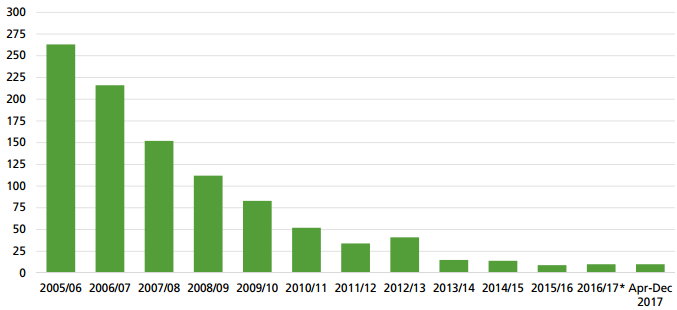

Figure 8: Number of clearance cases handled by The Pensions Regulator

Sources: TPR freedom of information release 2016-02-10: "Numbers of cases of clearance relating to corporate transactions"; TPR Compliance and enforcement quarterly bulletins from April 2017 onwards; *Committee calculation based on the above.

TPR handled 263 clearance cases in 2005-06, but just 10 in 2016-17. This does not reflect a marked decline in corporate activity, but a realisation on the part of companies and their lawyers that threats from TPR are hollow: it is a paper tiger. There is little incentive to seek clearance to avoid being subject to powers that TPR has very rarely deployed with success.

186. The Government cited Sir Philip Green's settlement with the BHS pension schemes as evidence that TPR's anti-avoidance powers can be effective.512 But that settlement was driven primarily by considerable public, press and parliamentary pressure. To stand independently in protection of pension promises, TPR needs to reset its reputation and demonstrate a marked break with hesitancy. Yet in evidence to us, TPR's current leadership defended its empty threats on Carillion, and displayed very little grasp of either which schemes were likely upcoming problem cases, or what TPR would do to protect the interests of members of those schemes.513 It is difficult to imagine that any reluctant scheme sponsor watching would have been cowed by TPR's alleged new approach.

187. The case of Carillion emphasised that the answer to the failings of pensions regulation is not simply new powers. The Pensions Regulator, and ultimately pensioners, would benefit from far harsher sanctions on sponsors who knowingly avoid their pension responsibilities through corporate transactions. But Carillion's pension schemes were not dumped as part of a sudden company sale; they were underfunded over an extended period in full view of TPR. TPR saw the wholly inadequate recovery plans and had the opportunity to impose a more appropriate schedule of contributions while the company was still solvent. Though it warned Carillion that it was prepared to do, it did not follow through with this ultimately hollow threat. TPR's bluff has been called too many times. It has said it will be quicker, bolder and more proactive. It certainly needs to be. But this will require substantial cultural change in an organisation where a tentative and apologetic approach is ingrained. We are far from convinced that TPR's current leadership is equipped to effect that change. The Work and Pensions Committee will further consider TPR in its ongoing inquiry into the Defined Benefit Pensions White Paper.

____________________________________________________________________

497 Q1285 [Esther McVey]

498 Work and Pensions Committee, Sixth report of session 2016-17, Defined benefit pension schemes, HC 55, December 2016

499 As above.

500 Work and Pensions Committee, Defined benefits white paper inquiry

501 Work and Pensions Committee, Defined Benefit Pensions

502 Q1285 and Q1304 [Esther McVey]

503 Letter from TPR to the Chairs, 16 March 2018

504 As above.

505 The Pensions Regulator, Corporate Plan 2017-2020, April 2017

506 The Pensions Regulator, Protecting Workplace Pensions, accessed 1 May 2018

507 Letter from TPR to the Chair, 13 April 2018

508 Q731 [Lesley Titcomb]

509 Q671 [Mike Birch]

510 This calculation would incorporate any mitigatory measures such as the transfer of assets. It also takes into account the relative strength of the sponsor covenants before and after the transaction.

511 These are known as "anti-avoidance" or "moral hazard" powers.

512 Q1293 [Esther McVey]

513 Q707, Q712, Q718 [Lesley Titcomb]