Computing Growth Benefits

Since Aschauer's (1989) seminal work on infrastructure, more sophisticated techniques have been developed to compute the short- and long-run effects of infrastructure on growth. Researchers have used monetary measures of public capital and/or investment (Devajaran et al. 1996) or physical stocks (Calderon and Serven 2004, 2010). Estimating the impact of infrastructure should address the issues of: (a) multidimensionality at the sector level, (b) improving the quantity and/or enhancing the quality of infrastructure, and (c) ameliorating issues of likely endogeneity and reverse causality.

Computing the growth benefits of narrowing the infrastructure gap in Sub-Saharan Africa is not trivial. It will depend on several factors, including (a) the economic approach used to examine this impact, (b) the infrastructure sectors included in the analysis, (c) the econometric techniques utilized, and (d) the sample of countries. This section uses the empirical estimation undertaken by Calderón and Servén (2010), that is, a cross-country panel data regression model that includes synthetic indicators of the quantity and quality of infrastructure. The analysis also uses other control variables that exert an influence on growth per capita, namely, education, financial development, trade openness, lack of price stability, government burden, institutional quality, and terms-of-trade shocks (see table 2.3). The econometric methodology and description of the instrument sets are summarized in box 2.3.

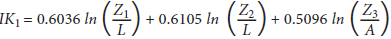

The synthetic measure of infrastructure quantity, IK1, is the first principal component of three variables: (fixed and mobile) phone lines per 1,000 people (Z1/L), electric power-generating capacity expressed in MW per 1,000 people (Z2/L), and the length of the road network in km per square km of arable land (Z3/A). Each of these variables is expressed in logs and standardized by subtracting its mean and dividing by its standard deviation. The three infrastructure stocks enter the first principal component with roughly similar weights:

We compute a synthetic index of infrastructure quality by computing the first principal component of the (arithmetic inverse of) electric power transmission and distribution losses as a percentage of output (Q2), and the share of paved roads in the total road network (Q3). The first principal component is defined as: IQ1 = 0.7071 ln (Q2) + 0.7071 ln (Q3).

Table 2.3 yields a positive and significant coefficient estimate for the infrastructure quantity index that is robust to the various sets of instruments used. Hence, expanding infrastructure quantity contributes positively to long-term growth-although the coefficient estimate is smaller when using external instruments than when using internal ones (columns [3] and [1], respectively). Furthermore, infrastructure quality also contributes positively to long-term growth. In this case, the coefficient estimate is larger when using external instruments than otherwise.

TABLE 2.3: Infrastructure and Economic Growth

Dependent variable: Growth in GDP per capita (annual average, percent), sample: 97 countries, 1960-2005 (non-overlapping 5-year period observations), GMM-IV system estimation

| Variable | [1] | [2] | [3] | [4] | ||||

| Infrastructure development (synthetic indexes) | ||||||||

| Infrastructure quantity (IK1)a | 2.6641 (1.105) | 2.1927 (0.981) | 2.260 (1.328) | 1.0609 (1.403) | ||||

| IK1 squared | .. | .. | -0.0403 (0.247) | .. | .. | |||

| IK1 * Sub-Saharan Africa | .. | .. | .. | 0.2897 (1.450) | ||||

| Quality of infrastructure services (IQ1)b | .. | 1.9581 (0.549) | 1.9373 (0.598) | 1.5233 (0.800) | ||||

| IQ1 squared | .. | .. | -0.0265 (0.298) | .. | ||||

| IQ1 * Sub-Saharan Africa | .. | .. | 1.3582 (1.281) | |||||

| Control variables | ||||||||

| Initial output per capita / per worker | -4.3056 | -6.2404 | -5.9773 | -5.2489 | ||||

| (logs) | (1.099) | (1.285) | (1.815) | (1.635) | ||||

| Education | 1.9914 | 2.7857 | 2.8253 | 2.9420 | ||||

| (secondary enrollment, logs) | (1.095) | (1.160) | (1.175) | (1.376) | ||||

| Financial development | 0.4856 | -0.0147 | -0.0231 | -0.0489 | ||||

| (private domestic credit as % of GDP, logs) | (0.605) | (0.492) | (0.508) | (0.640) | ||||

| Trade openness | 1.2705 | 1.0965 | 1.1278 | 0.9347 | ||||

| (trade volume as % of GDP, logs) | (1.053) | (1.410) | (1.380) | (1.363) | ||||

| Lack of price stability | -0.0990 | -0.0510 | -0.0511 | -0.0618 | ||||

| (inflation rate) | (0.036) | (0.033) | (0.033) | (0.031) | ||||

| Government burden | -1.3229 | -1.9217 | -2.0330 | -1.2706 | ||||

| (government consumption as % GDP, logs) | (1.274) | (1.281) | (1.297) | (1.363) | ||||

| Institutional quality | 0.4748 | -0.3029 | -0.2769 | 0.2056 | ||||

| (ICRG Political Risk Index, logs) | (2.418) | (1.735) | (1.632) | (2.408) | ||||

| Terms-of-trade shocks | 0.0197 | 0.0944 | 0.0991 | 0.0768 | ||||

| (first differences of log terms of trade) | (0.066) | (0.051) | (0.053) | (0.055) | ||||

| Observations | 582 | 582 | 582 | 582 | ||||

| Specification tests (p-values) (a) A-B test for 2nd-order serial correlation | (0.360) | (0.482) | (0.484) | (0.481) | ||||

| (b) Hansen test of overidentifying restrictions | (0.241) | (0.275) | (0.211) | (0.190) | ||||

| (c) Difference-Sargan tests | ||||||||

| All instruments for levels equation | (0.166) | (0.340) | (0.290) | (0.197) | ||||

Note: Numbers in parentheses are robust standard errors. The regression analysis includes an intercept and period-specific dummy variables. * (**) denotes statistical significance at the 10 (5) percent level. Standard errors are computed using the small-sample correction by Windmeijer (2005).

a. See Calderon and Serven (2010) for a definition of the synthetic indexes of infrastructure quantity and quality.

| BOX 2.3: Measuring the Impact of Infrastructure on Growth | The econometric technique used to estimate the impact of infrastructure on long-term growth is the system generalized method of moments (GMM) estimator (Arellano and Bover 1995; Blundell and Bond 1998), which combines the growth equation expressed in first differences-using lagged levels of the regressors as internal instruments-and in levels-using lagged differences of the regressors as instruments. In addition to internal instruments (lagged levels and differences of the regressors), the analysis also uses demographic and geographic variables as external instruments. The consistency of the system GMM estimator depends on the validity of the internal and external instruments. In turn, this is examined through two specification tests: first, the test of over-identifying restrictions (Hansen and Difference-Sargan tests), which tests the null hypothesis that instruments are uncorrelated with the estimated residuals. Failure to reject the null hypothesis gives support to the model. Second, the analysis uses tests of serial correlation of the residual, where the null hypothesis is that the estimated residuals of the regressions in differences do not exhibit second-order serial correlation. Again, failure to reject the null hypothesis gives support to the model. The standard errors of the efficient two-step system GMM estimator are significantly downward biased in small samples. The bias arises from the fact that the approximation to the asymptotic standard errors does not account for the extra small-sample variation due to the use of estimated parameters in constructing the efficient weighting matrix. Windmeijer (2005) proposes a correction that accounts for this fact. The correction term vanishes with increasing sample size and provides a better approximation in finite samples when all moment conditions are linear. Table 2.3 reports the GMM estimates of the parameters of the growth regression augmented by the synthetic indexes of infrastructure performance (quantity IK1 and quality IQ1, respectively). Columns [1] to [3] in the table report the coefficient estimates of the baseline growth regression equation including the synthetic quantity and quality indicators in the regression. This baseline specification is estimated using three sets of instruments for infrastructure: (a) lagged synthetic IK1 and IQ1 indicators (column [1]), (b) lagged values of the individual components of the synthetic indicators (quantity and quality of telecommunications, power, and transport) (column [2]), and (c) lagged values of external instruments, namely, urban population, labor force, and population density (column [3]). Source: Calderón and Servén (2010). |

Using the regression estimates in column [2] in Table 2.3, the growth effects of narrowing the infrastructure gap of Sub-Saharan African countries is computed. Two scenarios are presented: first, closing the gap of the region as well as selected groups within the region relative to the world median (excluding Sub-Saharan Africa) of the infrastructure distribution. The second scenario involves closing the infrastructure gap relative to the world's top decile of the infrastructure distribution. Table 2.3 depicts the region's gap for the second scenario.