Chapter 1 Overview

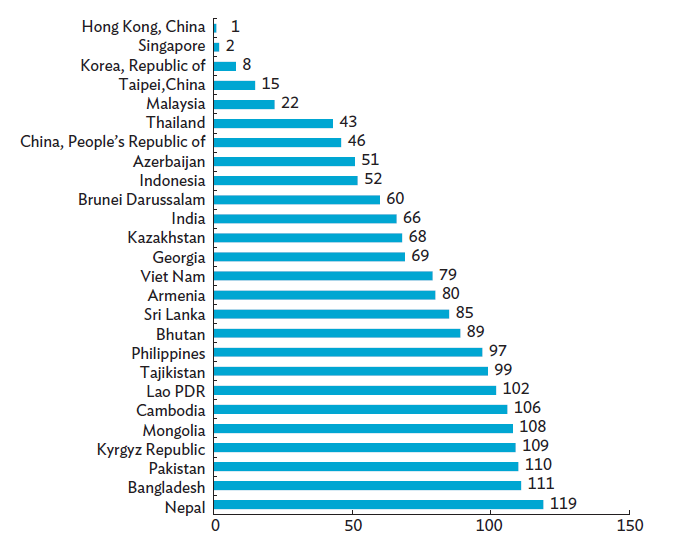

Developing Asia's remarkable economic performance since the 1980s comes in no small measure from its great strides in building infrastructure. Even so, the region still faces significant difficulties in delivering infrastructure services caused by the huge gap in infrastructure investment that translates into many unmet needs. Access to physical infrastructure and associated services remains inadequate, particularly in poorer areas. Over 400 million Asians live without electricity, 300 million without safe drinking water, and 1.5 billion without basic sanitation. And even those using these services often find the quality is inferior in both rural and urban areas. Notable problems are intermittent electricity, congested roads and ports, substandard water supply and sewerage, and poor-quality school and health facilities. The World Economic Forum's Global Competitiveness Report 2017-2018 shows that many economies in developing Asia are in the bottom half of the ranking on infrastructure (WEF 2017) (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1: Infrastructure Ranking of Developing Asian Economies, 2017-2018

Lao PDR = Lao People's Democratic Republic.

Source: World Economic Forum. 2017. Global Competitiveness Report 2017-2018. Geneva.

The infrastructure gap is the result of both a lack of financial resources and innovative and efficient channels to mobilize resources for desired development outcomes. While the need to build up infrastructure is widely recognized in the region, tight fiscal conditions and limited public sector capacity prevent most countries in developing Asia from making significant headway in narrowing their infrastructure gaps. A long sought-after solution has been to get the private sector to help fill the infrastructure gap. The private sector clearly has a lot to offer in many areas of infrastructure delivery, including improving operational efficiency, granting incentivized finance, promoting project innovation, and technical and managerial skills. An effective way for the private sector to maximize its comparative advantages is to redraw its relationship with the public sector to share roles and responsibilities in providing public goods and services more efficiently. To this end, the Public-Private Partnership (PPP) approach could transform how both sectors collaborate to deliver infrastructure services. The World Bank defines PPPs as "a long-term contract between a private party and a government entity, for providing a public asset or service, in which the private party bears significant risk and management responsibility, and remuneration is linked to performance" (World Bank 2017a). The Asian Development Bank (ADB) and the Inter-American Development Bank define PPPs similarly.

This book evaluates the major challenges that Asia must overcome to get more PPPs off the ground and to use these partnerships far more effectively than is currently the case. It examines optimal ways of sharing risk in these partnerships, proposes financial instruments that can promote private financing for PPPs, and suggests roles that multilateral development banks (MDBs) can play in mobilizing finance for PPPs. All these measures are powerful catalysts for bridging the risk gap that is holding back Asia's infrastructure development. The book presents country evidence and experiences from across the region to draw lessons and suggest ways for PPPs to unlock their potential for helping secure sustainable development. The Republic of Korea's considerable experience in implementing these partnerships holds many useful lessons-successes and shortcomings alike-for countries in developing Asia trying to increase private participation in infrastructure.