Risks in Investing in Infrastructure PPPs

Table 7.1 shows the results of a 2016 survey by ADB's Independent Evaluation Department of infrastructure investors in Asia ranking their risk perceptions (IED 2017).2 Most of the responses were from guarantors, who included export credit agencies, export-import banks, MDBs, bilateral development banks, specialized multilateral insurers, and private insurers. These institutions were overrepresented in the sample, while project sponsors and equipment providers may be underrepresented.

Table 7.1: ADB Survey Results on Infrastructure Investor Risk Perceptions in Asia

| Risk | Percentage of Respondents Indicating the Risk Is High |

| Payment risk on subsovereign borrowers/guarantors | 68 |

| Breach of contract | 67 |

| Payment risk on sovereign borrowers/guarantors | 62 |

| Country or political risks | 59 |

ADB = Asian Development Bank.

Note: The survey participants were asked what they thought were the most important risks or challenges in financing or investing in infrastructure projects in Asia.

Source: Independent Evaluation Department. 2017. Boosting ADB's Mobilization Capacity: The Role of Credit Enhancement Products. Manila: ADB.

The top three risks in Table 7.1 refer to governments, at the sovereign or subsovereign level, failing to meet their contractual obligations, especially their payment obligations. The top risk refers specifically to subsovereign borrowers. Since PPPs generally contain either direct payment obligations from governments, such as availability payments or contingent payment obligations, a negative perception of payment risk from government would be an obvious deterrent to private investors. The fourth risk more broadly states country or political risks, such as war, expropriation, civil disturbance, and breach of contract. In sum, the four highest risks relate to the sovereign counterparty in a PPP contract as opposed to commercial risks.

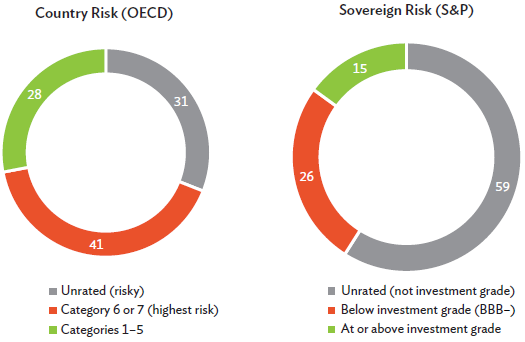

Figure 7.1 shows that 41% of ADB's 39 borrowing member countries are in the highest risk category based on the OECD's country risk classification (that is, categories 6 and 7).3 Considered equally risky are the 31% of countries that do not have an investment grade credit rating. The OECD's rating categories recommend minimum risk premiums for export credits, including guarantees. A higher risk category rating may ultimately translate into a higher interest rate, which reduces the financial viability of PPPs. A proxy for the interest rate can be derived directly from the risk premium charged by export credit agencies, which is based on this classification. More importantly, many banks will not lend to category 6 or 7 countries or, if they do, will either apply special scrutiny or only lend to PPPs that have hard currency revenues, such as oil wells and international airports.

Figure 7.1: Risk Profile of ADB's 39 Borrowing Member Countries (%)

OECD = Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, S&P = Standard & Poor's. Sources: OECD country risk classifications and S&P global ratings.

Using the S&P's sovereign risk definition, even more ADB borrowing member countries are considered risky (S&P Global Ratings 2017). In 2015, 26% of ADB's borrowing member countries were below investment grade (BBB-), while 59% were unrated and would, therefore, be considered risky by international lenders. S&P measures sovereign creditworthiness by scoring five key areas: institutional (how a government's institutions and policymaking affect a sovereign's credit fundamentals); economic (economic diversity and volatility, income levels, and growth prospects); external (external liquidity and international investment position); fiscal (fiscal performance and flexibility, and debt burden); and monetary (a monetary authority's ability to fulfill its mandate while sustaining a balanced economy and attenuating any major economic or financial shocks).

There is evidence that macroeconomic factors affect the bankability of PPP projects. Hammami, Ruhashyankiko, and Yehoue (2006), using the World Bank's Private Participation in Infrastructure Database, conclude that macroeconomic stability achieved through price stability, together with conducive market conditions, are associated with more projects being committed. A survey on the implementation of PPP infrastructure projects in Nigeria found that poor project bankability; unstable economic policies; and the weak financial, technical, and managerial capabilities of concessionaires were the main factors preventing projects from reaching financial close (Babatunde and Perera 2017).

Reducing risk profiles and having higher credit ratings can attract private investment since these drive investment decisions. Sovereign and country risks play an important role in predicting the number of PPPs reaching financial close and the size of private investments. In their empirical analysis using Euromoney's measure of country risk, Araya, Schwartz, and Andrés (2013) find that private sector participation in infrastructure projects is sensitive to country risk; that is, risk ratings are a generally reliable predictor of PPP investments in developing countries. An improvement in country risk scores has a positive effect, from 21% to 41%, on the probability of having PPP commitments as well as investments in dollar terms.4 Interestingly, the authors find the result consistent with all infrastructure sectors.

Using both OECD measures of country risk and S&P's definition of sovereign risk as independent variables, a regression analysis that uses the same methodology (Appendix A7.1 presents the regression framework) finds similar results to Araya, Schwartz, and Andrés (Table 7.2). Countries with higher country risk and lower S&P ratings can adversely affect the number of infrastructure PPPs reaching financial close (models 1 and 2 in Table 7.2). When macroeconomic indicators are introduced (models 3 and 4), the S&P rating loses significance. This result is intuitive since the rating is largely

based on macroeconomic indicators. Another major finding of the regression analysis is that the involvement of MDBs-through credit enhancement, for example-can significantly increase the number of projects reaching financial close (models 5 and 6). PPPs are assessed on a project-by-project basis and can, therefore, still be viable even though country risks are high, although they have a lower probability of being implemented.

Table 7.2: Regression Analysis on Country and Sovereign Risks Ratings to Number of Financially Close Infrastructure PPPs

| Explanatory Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 |

| -0.442 *** |

| -0.548 *** |

| -0.580 *** |

| |

| (0.087) |

| (0.212) |

| (0.172) |

| |

| S&P's sovereign rating |

| -1.171 ** |

| -0.772 |

| -1.262 |

|

| (0.670) |

| (0.912) |

| (0.878) | |

| GDP growth |

|

| 0.034 *** (0.013) | 0.034 *** (0.013) | 0.029 *** (0.011) | 0.030 *** (0.011) |

| Inflation |

|

| -0.088 (0.054) | -0.088 * (0.053) | -0.067 (0.049) | -0.078 * (0.046) |

| Trade |

|

| 1.227 * | 1.293 ** | 1.241 * | 1.203 ** |

| openness |

|

| (0.726) | (0.560) | (0.691) | (0.539) |

|

|

|

|

| 0.127 *** |

| |

| participation |

|

|

|

| (0.024) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 0.629 *** | |

|

|

|

|

|

| (0.101) | |

| /lnalpha | -0.654 | -0.156 | 0.283 | 0.606 | 0.181 | 0.474 |

|

| (5.814) | (5.624) | (6.593) | (5.269) | (6.263) | (5.254) |

| Constant | 3.401 *** | 2.489 *** | -0.341 | -2.298 | -0.739 | -1.963 |

| project | (0.455) | -0.639 | (1.451) | (2.212) | (1.513) | (2.053) |

| Observations | 964 | 800 | 892 | 762 | 892 | 762 |

| Number of countries | 107 | 66 | 98 | 64 | 98 | 64 |

GDP = gross domestic product, MDB = multilateral development bank, OECD = Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, PPP = public-private partnership, S&P = Standard & Poor's.

Notes:

1. Standard errors in parentheses.

2. OECD country risk: 1 if a country has lowest risk and 7 if highest.

3. S&P rating: 1 if a country is below investment grade (BBB-) or unrated and 0 otherwise. *** p<0.01 ** p<0.05 * p<0.1

Source: Author and Mai Lin Villaruel.