Government Support to Reduce Risk in Infrastructure PPPs

Even though investors face high risks with infrastructure PPP projects in developing countries, measures can be taken to reduce and share these risks. Risk allocation is a vital element in structuring PPP projects in developed and developing countries. The literature suggests that risks should be allocated to the party best able to affect the risk factor, influence the sensitivity of a project to the risk, and absorb the risk (Irwin 2007).

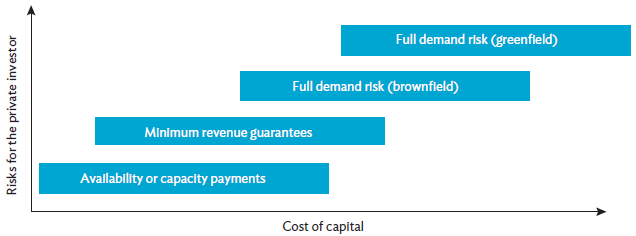

Because of the high risk, governments offer many forms of support for PPPs in Asia. The most common are land acquisition and resettlement costs, minimum demand and revenue guarantees, payment obligation guarantees, currency inconvertibility and transferability risk guarantees, and credit guarantees. Other forms of support include viability gap funding and grant funding at financial close to be used during construction (though this is usually limited to a percentage of a project's capital cost and given on a case- to-case basis). Figure 7.2 shows the modalities for allocating demand risk in PPP projects, with the highest risks for the private investor at the top of the chart. For investors, there is generally a direct relationship between risk and return. The figure shows the conceptual relationship between demand risk and the cost of capital, with availability or capacity payments allocating the least amount of risk to private investors. Full demand risk for greenfield projects without reliable data has the highest amount of risk for investors.

Figure 7.2: Modalities for Allocating Demand Risk in PPP Projects

Source: Author.

Typically, one would expect projects to have a lower cost of capital when risks are reduced through government commitments to mitigate them through minimum revenue guarantees or availability payments. This lower cost of capital should translate into lower project costs, and ultimately benefit the government.

This is generally the case, but these commitments are only as good as the level of adherence to them by the government counterparty handling the PPP. As Timothy Irwin has put it, the government counterparty must be able to absorb the risk (Irwin 2007). The government counterparty could be a state-owned utility or bulk power supplier for a power PPP, a municipal utility for a water PPP, or a government contracting agency for a transport PPP.

Governments can improve the domestic investment climate by fostering greater transparency; combating corruption, particularly at the sector level; and improving investor and creditor rights and protection. Doing this can significantly reduce economic and political risks that would otherwise result in extremely high-risk premiums (Schwartz, Ruiz-Nunez, and Chelsky 2014). In the absence of improving the domestic investment climate, governments can offer explicit guarantees or performance undertakings. In Bangladesh, for example, the allocation of risk in power PPPs is designed to deal with skepticism in the private sector over creditworthiness and the ability of government counterparties to meet payments. Many power infrastructure projects in Bangladesh that reached financial close relied on the government recognizing the payment obligations of government counterparties as sovereign obligations in project agreements (ADB 2017).

Private investors, however, are sometimes unwilling to accept sovereign guarantees or similar support mechanisms because of poor credit ratings or high country-risk profiles. In the "weakest link" credit model used by many project finance rating methodologies, the sovereign rating is a ceiling beyond which the project cannot be rated, except with special justification. S&P, for example, states this in its methodology for project finance transactions.