Case Study: Making a Kenya Power Project Viable Using Partial Risk Guarantees

The following looks at how a sovereign partial risk guarantee was used for a PPP power project in Kenya. Kenya Power (previously Kenya Power and Lighting Company) is a professionally managed power utility, majority owned by the Government of Kenya and traded on the Nairobi Securities Exchange. After the 2008 global financial crisis, Kenya Power found it difficult to attract investors for power projects-a situation aggravated by the political unrest after the 2007 elections.

Despite this difficult operating environment, the company steadily improved its performance and, by 2010, had several power purchase agreements with independent power producers. But, because of droughts from 2009 to 2011, it did not have enough energy from its hydropower plants and had to contract emergency generation at a very high price-$0.321 per kilowatt-hour.

Having to use emergency generation was a heavy financial burden on Kenya Power, which decided to contract new thermal and geothermal generation capacity to reduce the reliance on emergency generation in the medium term. It earmarked four independent power producers to provide a solution to its power shortage (Kaçaniku and Izaguirre-Bradley 2015). Kenya's Thika Power Ltd. was one of these producers, and it was slated to design, build, operate, and maintain an 87-megawatt combined-cycle diesel plant. Revenue for Thika Power was to come from 20-year power purchase agreement with Kenya Power, the government counterparty for the power purchase agreement.

Because Kenya Power faced a cash shortage, and because of the election unrest, the Thika power project would not have been viable without credit enhancement from MDBs. The World Bank Group, through the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA) and the International Development Association (IDA), provided a credit-enhancement package to bolster financing for Thika Power and the other three projects.

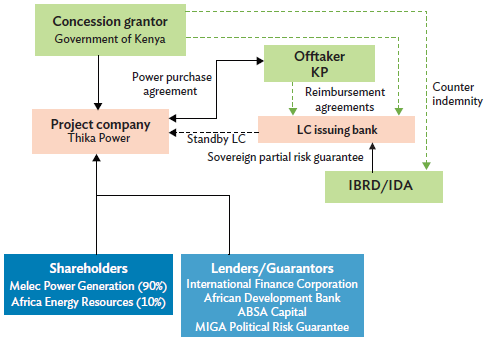

For credit enhancement, MIGA provided political risk insurance to cover termination payments for commercial lenders and sponsor equity, and IDA provided the partial risk guarantee with a letter of credit to cover Kenya Power's payment obligations under the power purchase agreement (Figure 7.4).

Figure 7.4: Partial Risk Guarantee Structure for Thika Power

IBRD = International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, IDA = International Development Association, KP = Kenya Power, LC = letter of credit, MIGA = Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency.

Source: Author.

MIGA's political risk insurance covered commercial lenders in case of termination and protected sponsors from political risk events, and had a term of 15 years to encourage longer-term lending. IDA's partial risk guarantee covered payment risk from Kenya Power. The letter of credit covered 3 months of capacity and energy payments and 2 months of fuel payments; the coverage was offered on a rolling basis. It would pay out automatically whether the payment was missed because of either Kenya Power's default or government interference. The letter of credit would also pay if there was a force majeure event preventing Kenya Power from meeting its obligations. The company had 12 months to repay the bank issuing the letter of credit before the guarantee was called. This mechanism ensured continuity for the 15-year period of support.

Thika Power and the other independent power producers receiving IDA's partial credit guarantees were the first independent power producers in Kenya to attract long-term commercial financing. Of the total $623 million funding for the four projects, $181 million was provided by commercial banks. For Thika Power, MIGA insured up to €81 million ($94 million). This supported local investors and added 298 megawatts of critically needed generation capacity.

An important factor for the success of this transaction was the two types of support provided by the multilateral agencies to the projects-MIGA covering the termination payment and IDA's partial risk guarantee through the letter of credit, which covered power purchase agreement payments and, through its triggering mechanism, ensured timely payments. Payment was due on demand on the basis of the verification process in the contract and did not need an arbitral award from an international court (Government of Kenya and IDA 2012).

Another success factor was that the guarantee cover reduced the government's contingent liabilities. If IDA's partial risk guarantee cover had not been given, the government would have had to provide an explicit sovereign guarantee to cover all of Kenya Power's obligations for the duration of the power purchase agreement. The alternative would have been for Kenya Power to provide its own cash collateral, which would have further strained its finances. Both options would have cost much more than the $35 million and €7.7 million ($9.1 million) in the letters of credit.

This case study shows several advantages of using sovereign partial risk guarantees, which in this case helped catalyze $623 million for four independent power producers in Kenya. A disadvantage of this product, however, is that a counter indemnity may be hard to obtain from governments who, possibly along with private sponsors, may not be aware of the advantages of sovereign guarantees. This makes capacity building necessary. Outside of this product, other solutions are available to deal with sovereign counterparty risk in PPP transactions.