Estimating the Benefits of a Multilateral Development Bank Partial Risk Guarantee

Large infrastructure projects are even more costly once risk-adjusted, while guarantees and complementary support from MDBs also increase PPP project costs by charging fees. The question is how to keep these costs as low as possible to reduce the cost of risk-adjusted PPP projects. Using a shadow bid financial model, this section presents the potential financial benefits, especially to governments, of an MDB partial risk guarantee. The model involves developing a shadow bid that provides an estimate of the annual service payments-the amount of revenue to cover all expected costs and provide the private partner with an attractive return-that the private sector would need to estimate before investing in a PPP project.

In a PPP project relying on government payments, the financial benefit to the government of using an MDB partial risk guarantee comes from a reduction in debt costs, enabling the project to raise financing at more favorable terms. The benefit will vary with the involvement of a sovereign counter indemnity by the host country. The sovereign country indemnity governs the repayment obligations in case the guarantee is called, and it allows the guarantee to be governed under similar conditions to sovereign loans with cross- default and cross-acceleration provisions. It also reduces the pricing of the guarantee when compared with private insurance markets.

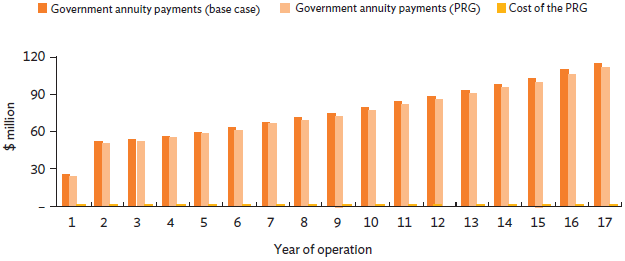

The following is an example of how an MDB partial risk guarantee can reduce the total cost to the government. In this scenario, the infrastructure PPP project's shadow bid financial model has the following specifications: a debt to equity ratio of 61:39, with 65% of total debt in United States dollars, which accounts for 40% of total funding (debt and equity). The total project cost is $300 million, and the country is below investment grade at BB- on S&P's rating. The rest of the debt consists of local currency lending from a state-owned financial institution (30%) and approximately (5%) from local commercial lenders. These project specifications were chosen because they represent a typical financial structure for which a guarantee may need to be provided in ADB's borrowing member countries, including a high amount of equity relative to developed markets and mixed financing in local and hard currencies. The partial risk guarantee provided by MDBs is estimated to reduce the cost of debt by 125 basis points for the hard currency portion of the lending. In most financial models, reducing the cost of debt will increase the project's equity internal rate of return. This is not realistic, however, because bidders would not require a higher return for a project that has a reduced risk. So, instead of increasing the project's equity internal rate of return, government annuity payments are adjusted downward, assuming the same rate of return and reflecting the reduced cost of funding. This is illustrated in Figure 7.5.

Figure 7.5: Government Annuity Payments with and without Multilateral Development Bank Sovereign Partial Risk Guarantees

PRG = partial risk guarantee.

Source: Author's calculations.

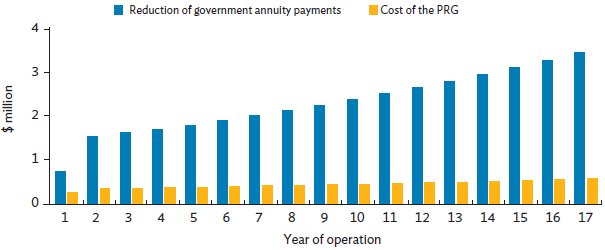

As Figure 7.5 shows, there is clearly an effective reduction in government annuity payments. The payments are higher under the base-case scenario relative to an MDB's partial risk guarantee. Figure 7.6 shows the reduction totaled $40 million, but it is associated with the total cost of the sovereign partial risk guarantee, amounting to $7.2 million during the years of operation. This cost is calculated based on ADB's published figures of a guarantee fee of 50 basis points and a commitment fee of 15 basis points. Thus, under the guarantee terms, a government could save $32.8 million (approximately 13% of the capital expenditure) from a project, which could lead to increased social benefits by allocating these savings to equally important public services. This example is illustrative and real savings can only be demonstrated by actually seeing the results of the tendering.

Figure 7.6: Estimated Financial Benefits of a Sovereign Partial Risk Guarantee

PRG = partial risk guarantee.

Source: Author's calculations.

It is important to note that the estimated financial benefits fully accrue to the government only if a partial risk guarantee is made available before bidding. This could be done through a letter of interest or as a stapled financing package offered by MDBs. This allows bidders to adjust their bids according to a project's reduced risk profile. When these guarantees come after the bidding, the financial benefits accrue largely to sponsors and lenders. The government, however, still benefits since this increases the likelihood of a project reaching financial close.

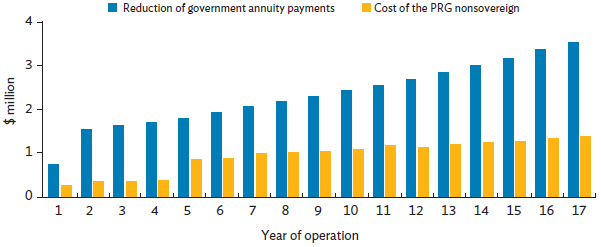

If a PPP project has a partial risk guarantee by an MDB but is not backed by a sovereign counter indemnity, the total cost of the guarantee for the years of operation would be higher at $18.2 million (Figure 7.7). In this case, the financial benefits from credit enhancement by an MDB tend to be lower, at $21.8 million or approximately 8% of capital expenditure. But, because many governments are not willing to offer sovereign counter indemnity, the net financial benefits of nonsovereign partial risk guarantees should be considered.

Figure 7.7: Estimated Financial Benefits of a Nonsovereign Partial Risk Guarantee

PRG = partial risk guarantee.

Source: Author's calculations.

In practice, the net financial benefits are expected to be larger than the examples presented for two main reasons. First, the model only considers effects that are certain. In the scenarios, debt will be reduced by an MDB guarantee and after receiving a guarantee, a sponsor, would at the very least demand a similar investment return. In reality, sponsors tend to bid more aggressively, thereby reducing their return in proportion to the reduction in risk. Second, the model assumes a constant debt-to-equity ratio. The level of debt is expected to increase as debt providers could cover a higher percentage of debt. A higher leverage would lower project costs for governments because debt is cheaper than equity. These effects would further reduce the government annuity payment. It should be noted that, in some countries, the amount of equity is mandated by law or regulation, which means the second argument would not apply.