Pro-Poor PPPs

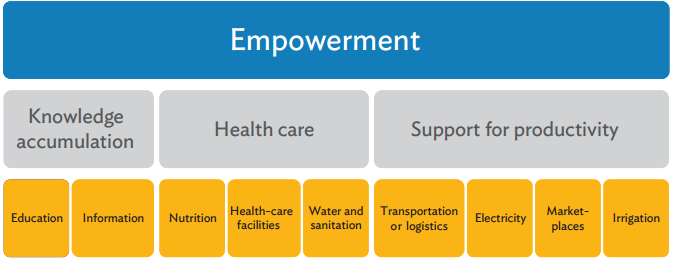

Building infrastructure accessible to the poor can have a transformational effect on empowering disadvantaged groups. Figure 11.4 shows the types of basic infrastructure that are fundamental for this process. Pro-poor PPPs do not differ much from other PPP modalities. Because output-based performance is a feature of a pro-poor PPP, the measures to gauge project success are straightforward. By contrast, traditional public procurement often uses variables that are neither necessary nor sufficient for measuring project success. For example, the cost of capital from a state budget is always considered zero, and therefore, no comparison can be made with a project's opportunity costs. Another example is when risks, especially future or contingent risks, are not monetized and included in the total project cost. This makes it incomparable with other modalities, such as privatization.

Figure 11.4: Basic Infrastructures for Empowering People

Source: Author.

The need to expand pro-poor infrastructure in Southeast Asia is huge, particularly in health, education, and water and sanitation, where development indicators are lagging behind. In education, Southeast Asia is underachieving in primary enrollment (Brunei Darussalam, Indonesia, and the Philippines), and reaching the last grade (Cambodia, Indonesia, the Lao PDR, Myanmar, and the Philippines). Telecommunication, internet, and broadcasting infrastructure can be used to support both formal and informal education. Upgrading and expanding water and sanitation systems are sorely needed in many countries-a process that could be accelerated if there was greater private sector participation in delivering this infrastructure. In 2015, 300 million people in the region did not have safe drinking water and 1.5 billion lacked basic sanitation (UNICEF and WHO 2015). Bringing economic development to remote areas remains a challenge in much of Southeast Asia. According to IEA (2017), 65 million people, 10% of the region's population, are without access to electricity. Renewable and clean energy, and micro, small, and medium-sized power plants-all areas in which companies are active- can help meet this demand. The private sector has a role to play in developing conventional markets for goods where small producers and farmers have access to markets without having to rely on lengthy supply chains.

Progress made in increasing the participation of the private sector in these and other pro-poor infrastructure areas will not, in themselves, be sufficient to reduce poverty. For this to happen, infrastructure must be accessible to the poor to legally use without exclusion, and it must be affordable (and again, in a way that can be used or consumed legally). This infrastructure must also be efficient in that it offers no incentives for overconsumption.

There are no conflicting principles between pro-poor and other types of PPP systems because infrastructure projects fulfill the following three basic principles: First, the government must have a solid argument for investing in the infrastructure, which should benefit the economy. From a public sector standpoint, the cost-benefit analysis of an infrastructure project should use an economic rather than financial approach. But this analysis can, to some extent, cover pro-poor and other social aspects, which are typically intangible if the data and method permit. It is not important that financial cost-benefit analysis results show a negative net benefit, but it is important that the socioeconomic cost-benefit analysis is positive. If it is, governments are justified in investing in a project, subject to other spending priorities.

Second, government contracting agencies must understand PPP principles and procedures, especially on legal frameworks, contract management, risk sharing, fiscal support, and negotiating with private sector partners. Technical capacity can be outsourced if needed; this is a pragmatic approach to improve the capabilities of government, especially subnational governments who are directly responsible for local welfare. Contracting agencies should balance their socioeconomic objectives with private returns to achieve mutual benefits. And third, it is important that governments listen to the views of all stakeholders in a PPP project, especially users. Here, contracting agencies should understand the real condition and demands of users, particularly for pro-poor projects, where the government must be particularly sensitive to purchasing ability and the dynamics of migration.

Because a pro-poor infrastructure program is based on an output or outcome policy, it can be developed either by traditional procurement or a PPP as long as socioeconomic output is maximized. In theory, PPPs are more public resource efficient than traditional procurement because, by their very nature, they enforce market discipline (targeted beneficiaries rather than public subsidies), provide opportunities for knowledge transfer, and enhance transparency and accountability. A company participating in a pro-poor project shows that it is socially responsible, and pro-poor projects make economic sense because better welfare means a higher potential for project users to become consumers.

Having a sound economic cost-benefit analysis can increase transparency, improve understanding and skills, and enhance opportunities for having better mechanisms to choose the right project modality. The main challenge of this method is usually data availability and questionable methodologies. A flawless cost-benefit analysis, however, is not a requirement. But public discourses on planned infrastructure projects are needed because they are vital for project planning. Social sectors that are seen as having a large impact on reducing poverty and improving welfare include primary and secondary education, education- related services, health care, and public transport. Infrastructure projects in these sectors usually encounter the least resistance from stakeholders and the public because their benefits are clear-and these are best-suited for pro-poor PPP projects.

In Southeast Asia, huge financial resources will be needed to provide the basic infrastructure services to make meaningful inroads into reducing poverty-not only to build infrastructure but also to provide subsidies for the poor to be able to use these services. Reaching the poor and vulnerable in distant and isolated communities is especially expensive, and inadequate data on these groups makes it hard for them to be identified. There are two main ways to avoid the exclusion of the poor from using infrastructure services. First, PPP operators charge affordable prices for these services and receive payments from the government to sustain their businesses up to an amount agreed in their contracts; these are called availability payments. In the school infrastructure PPP project in the Philippines, private partners designed, financed, and built classrooms in return for a 10-year lease contract before the facilities were transferred to the government. The private partners received availability payments throughout the leasing period for the upkeep of the classrooms. And second, PPP operators charge the full price for a service, and poor consumers receive direct subsidies from the government to be able to use them.

The challenge of pro-poor PPPs is the low purchasing power of the end users, which means that project revenue streams cannot rely on user fees without government subsidies. Using subsidies as part of pro-poor PPP financing schemes may create the problems of mistargeting or inefficient allocation. Indeed, subsidies often end up benefiting the better-off rather than the poor because of poor targeting. The amount of subsidy is subject to negotiation, but once set, they are often difficult to adjust later.

Because pro-poor PPP projects require public funds, they need continuous government support throughout their life cycle. As such, they are investments in human capital to strengthen a country's socioeconomic foundations. Using PPPs for this purpose can also bring greater efficiency, transparency, accountability, and value for money to government poverty-alleviation programs. Realistically, however, it is unlikely that there will be many pro-poor PPP infrastructure projects in Southeast Asia in the medium term, because of budget constraints and the complexity of this modality. That said, PPPs can be pro-poor, as the following example from Indonesia shows.