After Years of Planning a Dedicated High-Speed Rail System, the Authority Has Now Pursued Every Option to Reduce Costs by Using Existing Infrastructure

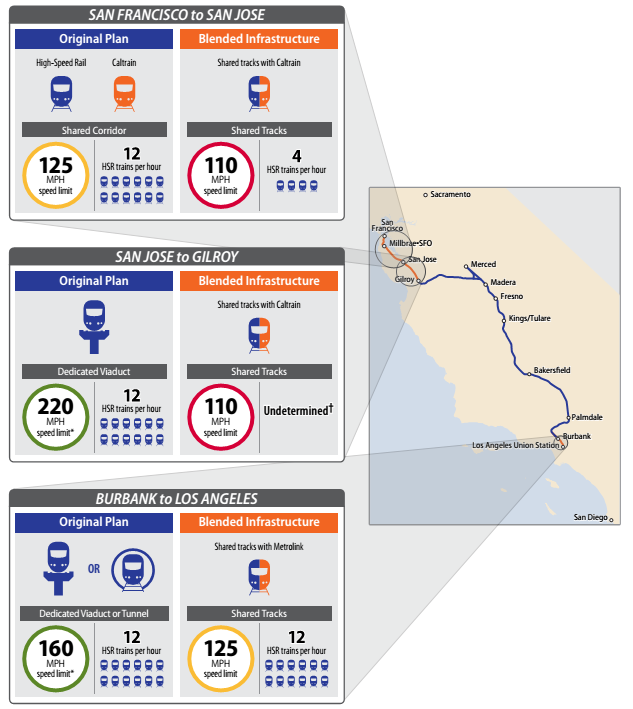

By incrementally modifying its plans for the high-speed rail system, the Authority reduced planned costs for some segments. However, these cost savings have also resulted in decreased service capabilities. When the Authority elects to blend a segment of the system by sharing existing rail corridor owned by another railroad, it significantly reduces planned costs by limiting the preparation needed to lay track. However, the Federal Railroad Administration sets a speed limit of 125 miles per hour for high-speed trains sharing a corridor or track with other rail traffic and of 110 miles per hour limit if the tracks intersect roads, which can be avoided by elevating tracks over or tunneling under roads. These blended segment speeds are significantly lower than those for dedicated high-speed segments of the system, where regulations allow speeds up to 220 miles per hour.

Further, sharing track means that high-speed rail trains must split time on the tracks with other operators, limiting how frequently high-speed trains can operate on a segment. For example, on the San Francisco Peninsula, sharing tracks with Caltrain means that the Authority can only operate four high-speed trains per hour, instead of 12 per hour, as it originally planned. The Authority similarly plans to share track between Burbank and Los Angeles with Metrolink, Amtrak, and Union Pacific Railroad (Union Pacific). Figure 5 shows how these limitations will affect eventual service options for the three segments where the Authority has implemented blending: San Francisco to San Jose, San Jose to Gilroy, and Burbank to Los Angeles.

Although blending a segment of the system by sharing existing rail corridor owned by another railroad will impose limitations on eventual high-speed rail operations, the extent to which the limitations will negatively affect actual rail service is not yet clear. | Although blending will impose limitations on eventual high-speed rail operations, the extent to which the limitations will negatively affect actual rail service is not yet clear. According to the Authority's deputy chief of rail operations, one reason why the limitations are not yet known is that service decisions, such as how fast and how frequently to operate the trains, have not yet been determined by the private sector operator that the Authority will select to run the system. Until the operator decides how many trains are needed, the Authority will not know the effect of sharing track. Similarly, although reducing speed limits imposes a restriction with which the train operator must contend, other service considerations also will influence how fast the operator will run the trains. For example, the distance necessary to safely accelerate or decelerate high-speed trains means that the trains may not be able to operate at 220 miles per hour in parts of the system even if speed limits allow it because of the need to navigate curves and stop in stations. |

Figure 5

The Authority Has Adopted Blending in Three Segments

Source: Review of the Authority's business plans, capital cost basis of estimate reports, preliminary and supplemental alternative analysis reports, preliminary engineering for project design reports, service planning studies, and additional cost estimates provided by Authority staff.

* Maximum speed limit shown; speed limited to 140 miles per hour in some segments.

† The Authority stated that it plans to run 12 trains per hour on this segment but did not provide us with any studies or agreements showing how it will accomplish this number.

We attempted to identify how the new speed limits have affected the Authority's projections of the blended segments' travel times, but the Authority was largely unable to provide any supporting documentation for the travel times it projected for these segments before 2016. Because the Authority had already implemented much of the system blending by then, it was generally unable to demonstrate how much time blending added to its travel time estimates. One exception was the segment between San Jose and Gilroy, for which the Authority did not adopt blending until 2018. For this forty-mile segment, the projected travel time increased from fourteen to eighteen minutes when the Authority switched from a dedicated line to shared track, decreasing the maximum speed for this segment.

Blending has allowed the Authority to expedite the system's planned time for construction, but the effect of those time savings may be offset by the Authority's past decisions to continue to study dedicated options. | Blending has allowed the Authority to expedite the system's planned time for construction by eliminating the time needed to design and build tunnels, viaducts, and other dedicated infrastructure, but the effect of those time savings may be offset by the Authority's past decisions to continue to study dedicated options. Rather than adopting a blended model for as much of the system as possible early on, the Authority has incrementally accepted blended alternatives over the past six years. As of 2012, the Authority planned to construct two new, dedicated tracks, including tunnels and viaducts, between San Jose and San Francisco. Rising cost estimates for this section contributed to the $98 billion system cost the Authority reported in its draft 2012 business plan. To address the rising costs and local governments' concerns about the potential impacts to environmental and community resources on the Peninsula, the Authority proposed a blended model in its revised plan. Shortly thereafter, the State Legislature mandated for this segment that the Authority could not use state funds to expand beyond Caltrain's existing tracks in the corridor. In its revised 2012 business plan, the Authority reported the segment's estimated costs had decreased from $13.6 billion to $5.6 billion, or 59 percent, after it adopted the blended approach. Table 2 provides the Authority's estimates for the decreased costs of the blended segments, which have partially offset increases in its systemwide cost estimates. |

|

Despite its adoption of the blended model in its 2012 revised business plan for one segment, the Authority continued to study dedicated options for at least two more years and did not begin studying a blended option in Los Angeles until 2015, limiting the time savings it might have realized had it acted more quickly. In 2012, the Authority's original plans for Burbank to Los Angeles called for either a tunnel under central Los Angeles or an aerial viaduct-similar to a bridge-running through it. In its May 2014 analysis document supporting the 2014 business plan, the Authority was still planning for dedicated options including a tunnel, ground-level track, and viaducts. The Authority did not introduce the blended, shared-track model for this segment in its planning document and business plan until 2016.

Table 2

Blending Significantly Reduced Planned Costs for Affected Segments (Dollars in Billions)

| EFFECTS OF BLENDING | |||

| COST | CHANGE | ||

SEGMENT | BEFORE | AFTER | AMOUNT | PERCENTAGE |

San Francisco to San Jose | $13.6 | $5.6 | -$8.0 | -59% |

San Jose to Gilroy | 4.4 | 2.8 | -1.6 | -36 |

Burbank to Los Angeles | 2.9 | 1.6 | -1.3 | -45 |

Source: The Authority's published business plans, budgets, and internal planning documents.

Note: This table only reflects cost estimates before and after blending was implemented on each segment in order to demonstrate the effect of blending on costs. Other factors, such as a reduction in the planned number of bridges in a segment, have lowered cost estimates after the implementation of blending.

The Authority's Southern California regional director confirmed that the Authority did not seriously begin studying a blended option for Los Angeles until 2015, when it procured a new planning contractor, and that it waited this long to ensure the blended model would not have unexpected consequences. Additionally, the regional director stated that because very little funding was available during this time period, the Authority could not conduct the study of the blended option. However, the 2012 revised business plan states that the Authority's position is that the system's benefits will be delivered faster through the blended approach. We therefore question why it waited three years to begin studying the blended option in Los Angeles to determine whether it was viable. Had the Authority acted earlier, it could have captured more of the time savings blending represents. For example, the Authority's 2012 decision to use blending on the San Francisco Peninsula has led to construction already beginning in that location. By comparison, the Authority has yet to finalize its planned route between Burbank and Los Angeles.

Although the process took several years, the Authority states it has now adopted blending in every segment of the system where sharing infrastructure is possible. In its 2018 business plan, it indicated for the first time that it intends to blend the segment between San Jose and Gilroy by operating within existing freight corridors and possibly sharing track with other carriers. Because the Authority is already pursuing blending on the San Francisco Peninsula and in Los Angeles, its chief of rail operations asserted that no further blending options are available. Additionally, he stated that travel time requirements mean that the Authority cannot implement additional blended segments even if opportunities become available. State law requires that the system be designed to achieve a nonstop travel time from San Francisco to Los Angeles Union Station of two hours and 40 minutes; according to the Authority's model, the travel time incorporating the current level of blending is expected to be two hours, 36 minutes, and 56 seconds.

Our review similarly noted that the blending of additional segments is unlikely because of characteristics of the remaining segments. For example, the only existing rail line traversing the Tehachapi Mountains in Southern California is a winding freight line built in the 1870s. In the north, where the Authority plans to connect the Central Valley to the Bay Area via the Pacheco Pass, no current rail system exists. In both regions, the Authority plans to pursue complicated tunneling projects that include tunnels over 20 miles long and more than 2,000 feet underground.

Our analysis shows that the Authority's cost estimates would have increased by 111 percent since the publication of its 2009 business plan had the Authority not implemented blending; instead, overall costs have increased by 81 percent. | Blending has allowed the Authority to partially offset significant cost overruns for the system as a whole. Our analysis shows that the Authority's cost estimates would have increased by 111 percent since the publication of its 2009 business plan had the Authority not implemented blending; instead, overall costs have increased by 81 percent. However, the fact that the Authority has now exhausted all blending options limits its ability to mitigate the effects of future cost overruns through additional blending. |

|