What this investigation is about

1 In the next 10 years, the Ministry of Defence (the Department) plans to invest £46 billion purchasing and supporting front-line aircraft, including the helicopters and fast jets used by the Royal Navy, British Army and Royal Air Force (RAF). Every five years, through Strategic Defence and Security Reviews, the government sets the strategic context which informs the Department's assessment of the aircraft and aircrew required. It most recently conducted a review in 2015. This increased current aircrew requirements compared with the previous 2010 review, leading to a 29% (76) rise in students needing to complete training in 2018-19. This increase resulted from, for example, introducing two further Typhoon squadrons; accelerating the purchase of F-35 jets; and committing to buy new maritime patrol aircraft and remotely piloted aircraft.

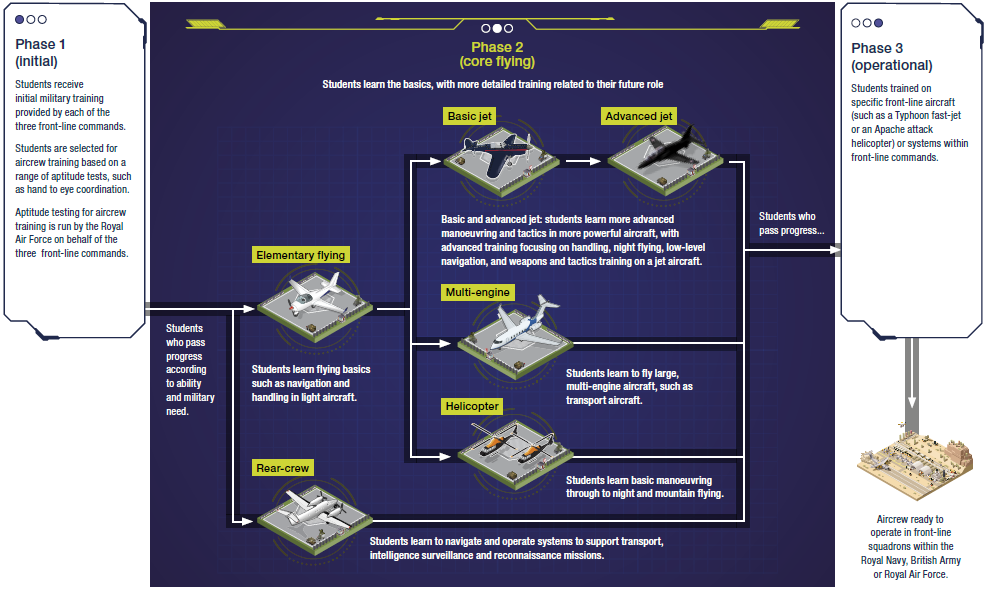

2 To operate this equipment, the Department must train enough aircrew with the right skills. These aircrew include pilots, observers and weapons specialists to fly the aircraft and operate its systems. For aircrew to be able to serve in front-line squadrons, they must complete a three-phase training process (Figure 1 overleaf).

3 The Department currently provides Phase 2 - core flying training - through a range of providers. They include Ascent Flight Training (Management) Limited (hereafter Ascent) as the principal partner, with whom it contracted in 2008 to design, introduce and then provide, with the Department, a new Phase 2 training system. This became known as the Military Flying Training System (MFTS).

4 Since 2012, the Department and Ascent have been transitioning to MFTS from legacy training. The Department considers the MFTS, alongside changes to front-line aircraft, to represent the largest transformation of UK military flying in more than a generation. Through the MFTS, the Department aims to:

• optimise aircrew training time;

• close the gap between the skills that aircrew have on finishing Phase 2 training and those they need to operate front-line aircraft; and

• reduce the overall cost of flying training.

____________________________________________________________________________________________

Figure 1

Military flying training model, as at July 2019

The aircrew training model involves three phases with separate training for different aircraft and aircrew

Source: National Audit Office

____________________________________________________________________________________________

5 Ascent has been contracted to provide the Department's earlier 2010 Review aircrew requirements, rather than the higher requirements of the 2015 Review.1 It is paid for designing and delivering the MFTS, and then for making available training components across a range of training packages, including for helicopters and fast jets. These courses cannot be provided if either the Department or Ascent, or their supply-chains, do not meet their contractual responsibilities. As shown in Figure 7, these responsibilities include providing flight simulators and aircraft, and managing airfield services. As at 2015, the Department had forecast the MFTS would cost £3.2 billion during the 25-year contract, and up to 31 March 2019 Ascent had received £514 million.2

6 In 2015, we reported that full introduction of the MFTS had been delayed nearly six years with the expectation that it would operate at full capacity by December 2019.3 This followed several events which affected the Department's original assumptions and which took time to resolve. They included the Strategic Defence and Security Review 2010 approximately halving the number of student recruits each year, and reductions in funding affecting how the Department would purchase aircraft. In our 2015 report we recommended that the Department better incentivise Ascent to meet the MFTS aims, establish a baseline against which to assess performance, and examine the time and cost implications of increasing training capacity across the system. Subsequently, the Strategic Defence and Security Review 2015 increased the demands for trained personnel.

7 This investigation follows up recent Parliamentary concerns about the MFTS.

It builds on our 2015 report by describing what has been delivered, while setting this within the broader context of the Department's current aircrew requirements and its overall training system. It describes:

• the Department's aircrew requirements, the three-phase training process and how this is performing (Part One);

• what has been delivered as part of the MFTS and the system's performance (Part Two); and

• the Department's actions to address flying training shortfalls (Part Three).

8 We conducted our fieldwork in June 2019 by interviewing Department and Ascent staff; reviewing available data on training and aircrew requirements; and examining performance reports. Appendix One describes our approach. We do not consider the value for money of military flying training.

9 As the report highlights, in a number of places we identified significant gaps and inconsistencies in data used centrally by the Department to manage the training process. The central team, which oversees Phase 2 training, also oversees RAF training, with Navy and Army Commands having responsibility for their respective students. Centrally, the Department does not collate data from front-line commands other than the RAF. This includes, for example, on the time students take to complete their three-phase training.

______________________________________________________________________

1 The Department has taken time to consider how it will deliver the increased requirements set by the 2015 Review.

2 Figures provided by Ascent. They cover the design and delivery of the MFTS, alongside debt repayments for fast jets and fixed-wing training private finance initiatives. They do not include more than £400 million of Departmental capital repayments direct to sub-contractors for aircraft and other infrastructure to support training.

3 Comptroller and Auditor General, Ministry of Defence: Military flying training, Session 2015-16, HC 81, National Audit Office, June 2015.