1.2. An Approach to Managing Risks while Encouraging Investments

Despite the promises and opportunities associated with PPPs, clearly some challenges remain. These difficulties arise because risk sharing can be complicated due to information asymmetries. The first set of issues relates to the private partner's ability to mask the project costs and the amount of effort extended. Thus, the private party has incentive to renege on contracts, or at the minimum, to hide the effort and costs of its provision. Section 2 examines these issues, where we use a sectoral perspective to examine the potential to hide information and renege on commitments.

A second set of difficulties concerns the overall public finances at different levels of government-particularly, the government's ability to manage current and future liabilities. As the bulk of PPP investments are likely to involve subnational governments that tend to have limited own-sources of revenue, there is a tendency to "kick the can down the road" or pass it off to upper levels of government.

Clearly, from an investor's perspective, the credibility and sustainability of government finances are critical considerations when making sound investment decisions. Given that PPP investments are increasingly being undertaken at the subnational level, the generation of accurate and timely information on general government liabilities (including all levels of government and public enterprises) becomes a critical element in assessing investment sustainability, especially where cross-border investments might be involved. These issues are discussed in Section 3.

In general, the absence of standardized and timely information on the buildup of liabilities is likely to have two distinct effects. In boom periods, this is likely to lead to "irrational exuberance" and the generation of inadequate and unsustainable investments. Problems are likely to be magnified at the subnational level, especially in the absence of effective own-sources of revenue or incentives to ensure that the liabilities will not be passed on to the center, Brussels (in the case of the EU) or future generations.

The obverse is likely to be a greater problem in developing countries: investible capital fears to tread in areas where the enabling environment is problematic. Thus, even though standardized information on subnational operations is absent in Canada, the expectation is nevertheless that since they have own-source revenues and the federal government is not likely to intervene, the local governments will "behave well." This would clearly not be the case if effective hard budget constraints were lacking, as may be the case at the subnational level in most developing countries, e.g., China.

Indeed, the risk management framework needs to be sufficiently flexible to accommodate excess private liabilities that are translated into public liabilities-e.g., as seen in the US subprime crisis, or the excess building in Ireland and Spain (both countries had been praised by the IMF for fiscal prudence prior to the 2008 economic crisis). In Europe, the presence of a supranational tier likely blinded markets to the risks involved in specific countries (especially in southern Europe, from Portugal and Spain to Greece). It is not enough to assume that hard budget constraints exist and that markets will adequately assess and discount the risks involved in specific investments. Consequently, the empty buildings in Spain are reminiscent of the late-1990s Asian crisis, or the earlier difficulties in Latin America.

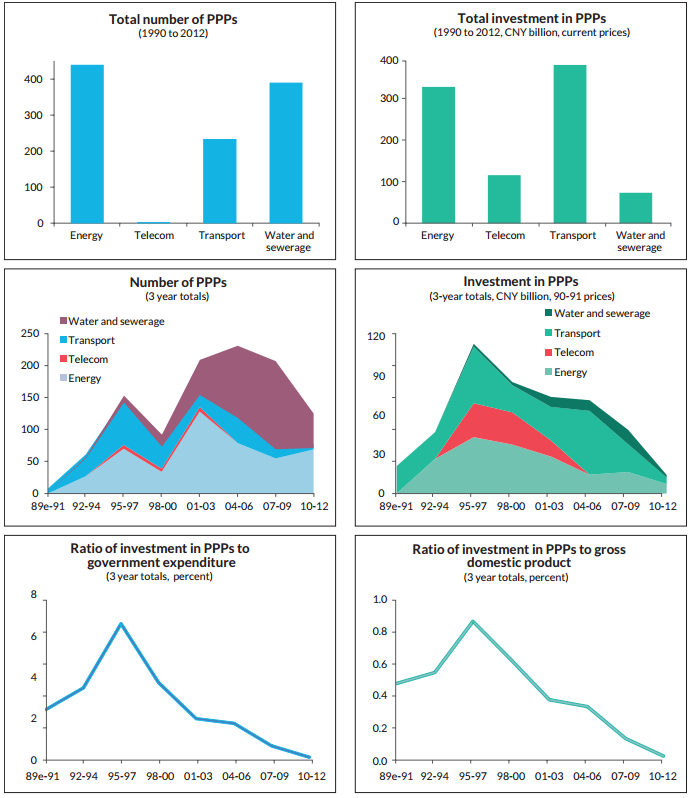

Figure 4. Snapshot of PRC's Infrastructure PPPs

e = estimate

Notes: The data indicate the number of PPP projects and the value of investment committed to by the project. Data for 1989 are estimated as the average of 1990 and 1991 values. Constant price estimates use the gross domestic product deflator. The data indicate that PPPs involving a private partner, where state-owned enterprises or their subsidiaries remain majorly owned by government entities are not considered as private sponsors.

Source: Asian Development Bank (2013).