1.5 An overview of operational social infrastructure PPP projects in Australia and New Zealand

Early PPP projects, in the 1990s, were organised in a similar way to the Private Finance Initiative (PFI) projects implemented by the UK Government. These early social infrastructure projects included hospitals, prisons and public facilities such as sporting stadia.15 These projects passed full responsibility for the provision of services and financing the capital cost associated with infrastructure to the private sector. Initial concerns with the full outsourcing of public services were outweighed by the advantages of the private sector bringing best international practice, sound management principles, financing and whole- of-life thinking to the delivery of quality infrastructure and services.

New PPP policies were released in Australia and New Zealand from 2000, with a different balance of government and private sector roles. Governments typically retained responsibility for the actual delivery of public services to the community, with the private sector 'owning'16 and financing capital facilities and providing support services like facilities management and sometimes cleaning. The general contractual phase used for this style of PPP is 'Design, Build, Finance and Maintain' (DBFM). It is this style of PPP project that this study concentrates on and a full list of the projects undertaken in New Zealand are detailed at Table B.1 and Australian projects are detailed at Table B.3 in Appendix B.

Such PPP projects gained wide acceptance until the impacts of the Global Financial Crisis of 2007-08, which impacted access to finance. In response, governments sought to optimise the value obtained from PPP structures by retaining the positive features of PPPs (for example, transferring ownership risks and FM services) and reducing the long-term debt burden on private financing17 by making contributions to the capital cost of facilities once commercial acceptance was gained.

Since about 2015, there have again been examples where the private sector has taken responsibility not only for DBFM but also operations. Examples include the Wiri Prison in New Zealand and Ravenhall Prison in Victoria.

All projects delivered since 2000 have adopted sophisticated contracts whereby service outcomes are driven by the contracts using KPIs or 'Key Result Areas,' and the application of abatement regimes if areas of the required service are not met by the PPP special purpose vehicle (SPV).18

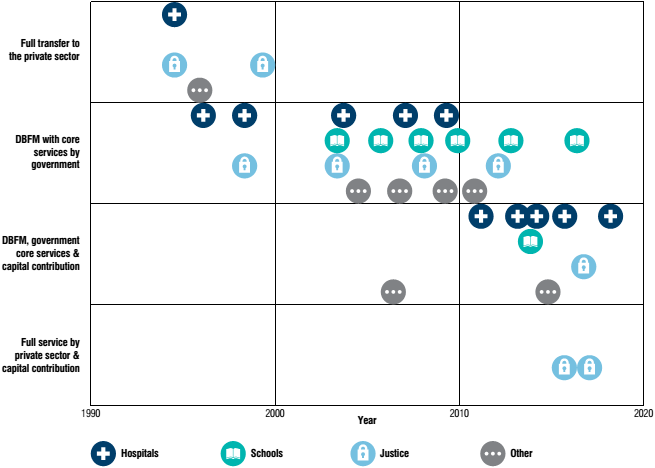

There is no single contract or service or contract model for PPP projects that has been used consistently over time. Variants or styles of the model are used by different jurisdictions to suit their individual requirements and appetite for risk allocation. Four apparent styles of Australian and New Zealand PPPs for social infrastructure are depicted in Figure 1 and detailed below.

1. The full transfer to private sector model represented a complete transfer of all core and non-core services, including all project risk to the private sector.

2. The DBFM with core services by government model represents transfer of all non-core services along with facility design, build, finance and maintain to the private sector. The projects undertaken before 2000s using this model routinely transferred most of the project risk of the facilityand non-core services to the private sector. However, from 2000 onwards, PPP policy and practices were revised to ensure the 'optimum risk allocation' principle (a risk is assigned to the party best able to manage it) is applied.

3. The model of DBFM with government delivering core services and also making a capital contribution represents transfer of all non-core services along with facility design, build, finance and maintain to the private sector. The objective of upfront capital payments by government was to minimise fiscal risk, lower cost of PPP contracts and improve public-sector flexibility.

4. The full service by private-sector model again represents complete transfer of core and non-core services to the private-sector. Recently there have examples where justice sectors across both Australia and New Zealand have undertaken prison projects using this procurement model. The difference between this approach and that adopted in the 1990s is the greater level of management control through the use of KPI regimes and the potential for a capital contribution from government.

Given that the focus of this study is to understand whether the current styles of PPPs are meeting the original service expectations during their operational phase, it is reasonable that the sample of this study is drawn from projects since 2000, and where the facility has been in operation for at least three years.

Figure 1: Timeline of the four styles of social infrastructure PPPs in Australia and New Zealand since the 1990s19