B.1 A case for PPP evaluation in the operational phase

This section of the report summarises relevant literature and considers the maturity of PPP projects in Australia and New Zealand from a service recipient's perspective. A longer review of literature is detailed in Appendix B.2.

The public sector engages the private sector to either deliver some or most of the project elements for both social and economic projects. This process of contracting a project or parts of the project to the best capable party provides numerous benefits to the public sector. The arrangement between the parties to deliver specific project phases leads to the development of various procurement strategies. These procurement strategies vary widely in terms of (i) private sector engagement period, (ii) risk transfer profile and (iii) performance requirements.

The public-private partnership (PPP) procurement model is an arrangement between the public and private sectors to deliver social and economic projects. Typically, the private sector is responsible for project finance, design, construction, operation (to some extent) and maintenance for 25-30 years before the project facility is transferred back to the public sector at an acceptable (and contracted) standard. The private sector forms a special purpose vehicle (SPV) using various private sector organisations to deliver the project.

The key benefit to the public sector from using a PPP strategy is that private sector is not only responsible for the traditional design and construct of the project facility but also responsible to maintain and operate the facility at a required standard for many years. The payment for services only commences at the project's operational phase, which is based on certain pre-agreed key performance criteria (KPIs). If the service provider fails to meet the project KPIs during the operational phase, monies can be withheld based on non-performance of an expected service. Conversely, there are a number of examples where excellent service has been rewarded by contract extensions or the addition of major modifications to existing agreements, for example the Melbourne Convention Centre. These contractual mechanisms allow the public sector to ensure standards and quality are maintained as well as providing flexibility as needs change. In social infrastructure projects, services that are allocated to the private sector in the operational phase are generally non-core services for example: cleaning, catering, gardening, and facility maintenance. The allocation of non-core services to the private sector allows the public sector to focus on the delivery of core services (for example, education, health and justice).

The literature recognises and credits the UK as the birthplace of PPPs and related funding mechanisms. Introduced in 1992, the original form of PPP used in the UK was called the Private Finance Initiative (PFI). Like the UK, Australia and New Zealand have long histories of using PPPs for public infrastructure projects. In both Australia and New Zealand, the development of centralised PPP agencies and units within government Treasuries to develop standardised agreements, and to shepherd and oversee the use and implementation of the PPP model seems to be one of the key factors that have contributed to the success of the model.

The UK currently has 700 operational PFI contracts with a capital value of around £60 billion, which is the highest in the world (House of Commons Committee of Public Accounts, 2018). The PFI projects in the UK have been seen in recent years to have produced mixed performance outcomes. A 2017 study shows a substantial decline in the number of PFI projects undertaken by the UK Government over recent years (Benjamin & Jones, 2017), with a UK Government decision to abandon consideration of new PFI contracts in 2018 putting a halt to the approach in the years since. Cost efficiency, value for money concerns, limited risk transfer, lack of flexibility, long-term fiscal risk for taxpayers and operational complexity were cited as some of the concerns for the PFI model (HM Treasury, 2018).

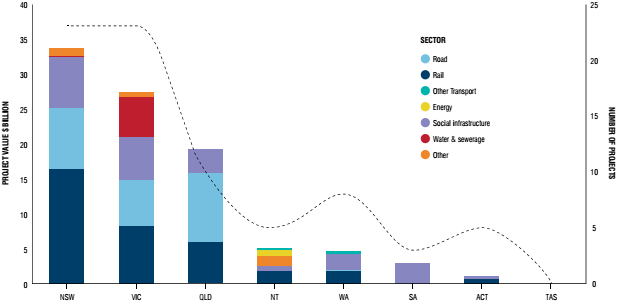

In Australia, the PPP procurement model is being utilised by most states and territories to deliver social and economic projects with Victoria and New South Wales being the leaders in the PPP market, refer to Figure B.1. The National PPP Policy and Guidelines documents provide a general set of guidelines to states and territories on the use of PPP procurement model (Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications, 2018). Victoria and New South Wales have developed some of the most robust PPP policy and practice guidelines over the years to ensure successful delivery of PPP projects.

The PPP procurement process in Australia has evolved from first generation to second generation type projects (Duffield, 2005). The first-generation type contracts from the early 1990s to late 1990s were the result of high public debt and reduced government appetite for new borrowings and were characterised by the comprehensive transfer of project risk to the private sector. This approach to risk transfer led to some project failures as some of the project risks were beyond the effective management of the private sector. The lessons learned gave birth to a second generation type of PPP contracts after the Second Review of The Private Finance Initiative by Sir Malcolm Bates in 1999 and development of Partnerships Victoria Policy in 2000 (Hodge & Duffield, 2010). The principle of risk sharing was applied, with the emphasis on risk being assigned to the party best capable of managing and mitigating that risk in the most cost-effective manner.

Figure B.1: Public Private Partnerships in Australia, by jurisdiction30

In 2009, there were 49 operational PPP projects with a capital value of AUD $32.3 billion in Australia (Palcic et al, 2019). Australian PPP projects generally enjoy a good reputation internationally for successful completion on-time and within budget. Australian PPPs are typically characterised by a focus on core services, payment for defined assets and services once delivered, financial accountability for lack of performance, access to private sector technical and management skills resulting from competition, access to private sector finance and innovation (Duffield et al 2008, Saeed 2018). However, there have been some notable failures (for example, Sydney's Cross City Tunnel and Lane Cove Tunnel, the Adelaide-Darwin Railway and Brisbane's Clem Jones Tunnel) due to lower than predicted revenue generation, which led to the insolvency of the SPV (Duffield 2008, PwC 2017).

PPP procurement in New Zealand is managed by the New Zealand Infrastructure Commission. This agency has overseen the implementation of a number of social and economic projects. The Auckland South Corrections Facility project is one of the most innovative PPP arrangement undertaken by the New Zealand Government in recent years. The New Zealand Government intends to use the PPP procurement model for future projects where value for money to taxpayers is evident (National Infrastructure Unit, 2010).

Literature examining the PPP projects in Australia and the UK is available, however there is limited publicly available analysis of New Zealand social infrastructure PPP projects. Table B.1 presents some of the major PPP projects in New Zealand.

Table B.1: Major PPP projects in New Zealand

| Major PPP projects in New Zealand | Description | Completion | Status |

| Hobsonville Schools PPP | Primary and secondary schools at Hobsonville Point, with education services provided by the Ministry of Education | 2013 | In operation |

| Auckland South Correctional Facility | Wiri Prison - a 960-bed men's prison, with custodial services provided by the PPP contractor | 2015 | In operation |

| Transmission Gully expressway | 27-kilometre expressway in Wellington | 2020 (estimated) | Under construction |

| Schools 2 PPP | A bundle of four schools in Canterbury, Auckland and Queenstown, with education services provided by the Ministry of Education | 2018 | In operation |

| Auckland Prison | New maximum-security facility and refurbishment of existing facility at Paremoremo Prison, with custodial services provided by the New Zealand Department of Corrections | 2018 | In operation |

| Puhoi to Warkworth Highway | 18-kilometre expressway in Auckland | 2022 (estimated) | Under construction |

| Schools PPP3 | A bundle of three primary schools in Auckland and Hamilton and two co-located secondary schools in Christchurch | 2019 (estimated) | Under construction |

| Waikeria Prison | A new 500-bed high security prison with an integrated 100-bed mental health unit | 2022 (estimated) | Under construction |

Numerous international studies conclude that the PPP procurement model has stronger incentives to minimise whole-of-life costs and improve service quality outcomes than traditional procurement approaches like Design and Construct or Construct- Only models (Hodge & Greve 2017, Saeed 2018). However, there is also a significant number of studies that have found issues in PPP projects with risk allocation, innovation and operational flexibility (Hodge & Greve 2017, Saeed 2018). It is therefore critical to evaluate outcomes of mature social PPP projects across Australia and New Zealand from the service recipients' perspective. The service recipients' unique perspective of mature social PPP projects should be able to shed light on performance issues faced by service recipients during operational phase.