1.1.2 The infrastructure surge is risky

One of the many responses to the pandemic has been the call for more infrastructure as stimulus.41 Public infrastructure spending is a traditional recourse when the economy tanks, for several reasons. One is the idea that construction not only props up employment, but in so doing it creates useful assets; road and rail upgrades facilitate the efficient movement of people and goods, leading to greater tax revenues down the track that help to pay for the infrastructure. A second reason is that stimulus-oriented construction can be wound back more easily once the economy is on a better footing,42 unlike, for instance, an increase to unemployment payments.

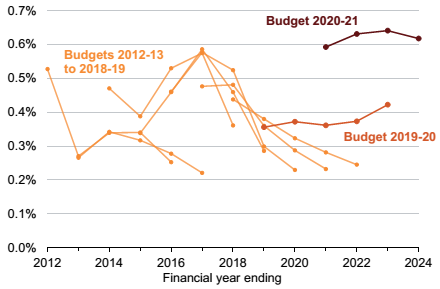

The Federal Government has responded to calls for infrastructure as stimulus. In its 2020 Budget, it steps up funding for transport to $11.5 billion in 2020-21, $12.7 billion the following year, then about $13.5 billion in each of the following two years.43 This is about one-and-a-half times the usual levels of funding from the Commonwealth (Figure 1.4). The Budget includes $750 million for Queensland's Coomera Connector Stage 1, and about $600 million each for upgrades to the New England and Newell Highways in NSW.44

Figure 1.4: Budgeted Commonwealth spending on transport is higher than ever

Estimated transport infrastructure spend, per cent of GDP

Source: Commonwealth budget papers.

Will this uptick in funding be an effective form of stimulus? There are three reasons for scepticism.

First, it's not a foregone conclusion that a public infrastructure project will be effective as stimulus. As leading fiscal policy expert Valerie Ramey puts it, 'details really matter'.45 In a comprehensive review of the fiscal responses since the Global Financial Crisis, she concludes that government infrastructure projects are not the best form of stimulus because they take a long time to get going.46 (That's not to say they couldn't be worthwhile in the longer run, provided the benefits outweighed the costs.)

A second reason for scepticism about infrastructure as stimulus is the capacity of the construction industry. Even before the pandemic, governments were worried about the industry's capacity to take on more work on top of the record quantity of works in general and megaprojects in particular that were under construction. According to the International Monetary Fund, 'project delays are longer if projects are approved and undertaken when public investment is significantly scaled up'.47

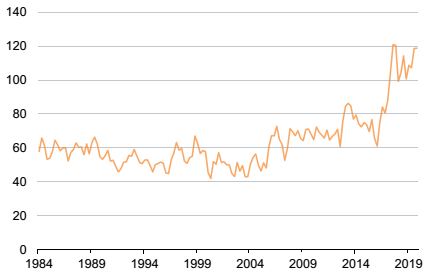

The number of people working in engineering construction surged by 50 per cent in the three years before the pandemic (Figure 1.5). The image people may have of construction work as unskilled is out of date; as leading urban economist Ed Glaeser puts it, 'big infrastructure requires fancy equipment and skilled engineers, who aren't likely to be unemployed'.48 During the mining boom, skilled labour and machinery were imported. But with national borders closed, this option is not available now or for the foreseeable future.

A third reason for scepticism about transport infrastructure as stimulus is that even before the pandemic, governments were already struggling to spend their budget allocations. Commonwealth allocations to the states for transport infrastructure were underspent by $1.7 billion in 2019-20.49 The Federal Government attributed this underspend to COVID-19 and the bushfires, yet it also underspent on transport infrastructure by about $2 billion over the preceding two years.50

Figure 1.5: More people are employed in engineering construction than ever

People employed in heavy and civil engineering construction, thousands

Source: ABS (2020a, Table EQ06).

In a recession, a sound micro-economic framework is one of the best protections we have. As the Productivity Commission has observed: 'If you build things solely for demand-side stimulus, you run the risk of wasteful spending. If you do careful project assessment, you can boost productive capacity and aggregate demand.'51

____________________________________________________________________________

41. For example: Kehoe (2020), Wright and Crowe (2020) and Albanese (2020).

42. IMF (2020, p. 32).

43. Commonwealth of Australia (2020a, Section 6, p. 37)

44. Commonwealth of Australia (2020b, pp. 131-132).

45. Smith (2020).

46. Ramey (2019).

47. IMF (2020, p. 37).

48. Glaeser (2016).

49. Commonwealth of Australia (2020c, p. 7).

50. Commonwealth of Australia (2019, p. 80); and Commonwealth of Australia (2018, p. 80).

51. Brennan (2020).